Clinical Data Science and Informatics

Technology and Practice

New technologies are disruptive and there is always a learning curve to figure out how to best use the new technology.

-

Paper and pen (or pencils) are a technology, just as much so a computer. The technologies we use shape how we live and how we practice our professions.

-

Consider how you might write or draw something differently, if you were using a pen (which could not be undone) versus a pencil, whose marks could be erased.

Electronic medical records are no different than any other new technology: it will have a negative impact on some aspects of care, positive aspects on others and it takes a bit of time to figure out how to best use them. That is, what we conceive of as an optimal medical record will change as we move from an analog (paper record) to a digital (EHR).

It is interesting to think about why we are collecting the documentation and how this influences what we choose to document.

When my childhood physician, David Sundwall, finished his training at Harvard Medical School around 1973 he joined his father’s (Val) family practice in Murray, Utah. At Harvard, David had been trained in creating documentation following Larry Weed’s SOAP notes. But he found his father keeping his medical records on 3x5 inch (7.6x12.7 cm) cards. David convinced his father to start writing SOAP notes, but I do think it is interesting to think of whether the 3x5 cards were sufficient at that time:

- The diagnostic testing was much simpler in 1973 compared to now

- The number of therapeutic choices in 1973 was much smaller compared to now.

As you work through the initial readings and move on to discuss more explicitly EHRs, I want you to be thinking about several questions:

- Why do people write? Do they write to document, to communicate, to facilitate their own thinking?

- How do the technologies we use to write with change how and what we write? If you keep a diary, for example, do you write differently if you use a word processor where what you write an easily be deleted vs writing in a physical diary?

To add your thinking on this, consider the history of writing itself. The technologies used for writing were shaped by the resources locally available: in Mesopotamia there was clay, in Egypt papyrus, in China bamboo.

Our oldest written records are from clay tablets found in Mesopotamia. Two points: First, once the tablet was dried, it was essentially immutable (also quite permanent, more written documents survie from Mesopotamia than from Egypt, for example). Second, the technology of writing, small linear marks (cuneiform) had limited expression.

In the west clay tablets were replaced by Egyptian papyrus.

Among its affordances, papyrus was durable, could be extended by adhering additional sheets, and allowed tests written on it to be amended, unlike hardened clay. The smooth surface made possible the development of curvy hieratic script, and the use of the brush facilitated the development of colorful illustration, of which Egyptian papyri offer some beautiful examples. (The Book, Borsuk A. MIT Press. p. 16)

With papyrus writing could now be corrected, expanded, and illustrated. But at the cost of being far less durable than clay tablets. The Greeks made two important contributions to writing

The Greek invention of the consonant-vowel alphabet assured the development of literacy and the shift from table to scroll….And, like Egyptian hieratic script, it was better suited to papyrus than clay, leading to widespread adoption of scrolls. This reliance upon papyrus led to another important Greek invention: the pen…The enhanced speed of writing in turn influenced the alphabet….[I]t bears noting that writing’s form and materials developed in dialogue with one another, even in the early stage, shaping the form of the book to both writers and readers. (ibid. p. 24)

China’s bamboo resulted in a radically different style of writing.

This preliminary form influenced the very shape of Chinese writing….The traditional Chinese style of writing from top to bottom arises directly from the book’s materiality—a bamboo slip was too thin to permit more than one character per line….Because scribes wrote with their right hands, blank slips were held to the left….Because the strips were so thin, scribes developed vertical ideograms that could be written more easily on them. Guozhong gives the example of the characters for horse and pig, both of which appear to be standing on their hind legs, rather than on the ground, as we might expect. In addition to fitting comfortably on their supports, figures for humans and animals also face to the left, indicating the direction in which writing and reading will proceed. (ibid. pp. 26-27)

Analog to Digital Transformation of Health

Australia is in the process of transforming from the analog delivery of healthcare to the digital delivery of healthcare. In the GP domain Australia has a long history of using EHRs. However, in specialist-care and hospitals Australia is a few years behind other countries. This gives us the opportunity to learn from the mistakes and successes of other countries, like the USA and the UK.

Robert Wachter, MD, is the head of medicine at the University of California, San Fransicsco (UCSF), one of the premier academic hospitals in the USA. In 2015 Dr. Wachter wrote a great book The Digital Doctor that was inspired by UCSF’s initial experience with their new EHR. (We will read excerpts from this book throughout the year.) In 2016, the UK government asked Dr. Wachter to chair a study of the use of information technology in the UK. (You can read the report here.)

What does an EHR look like?

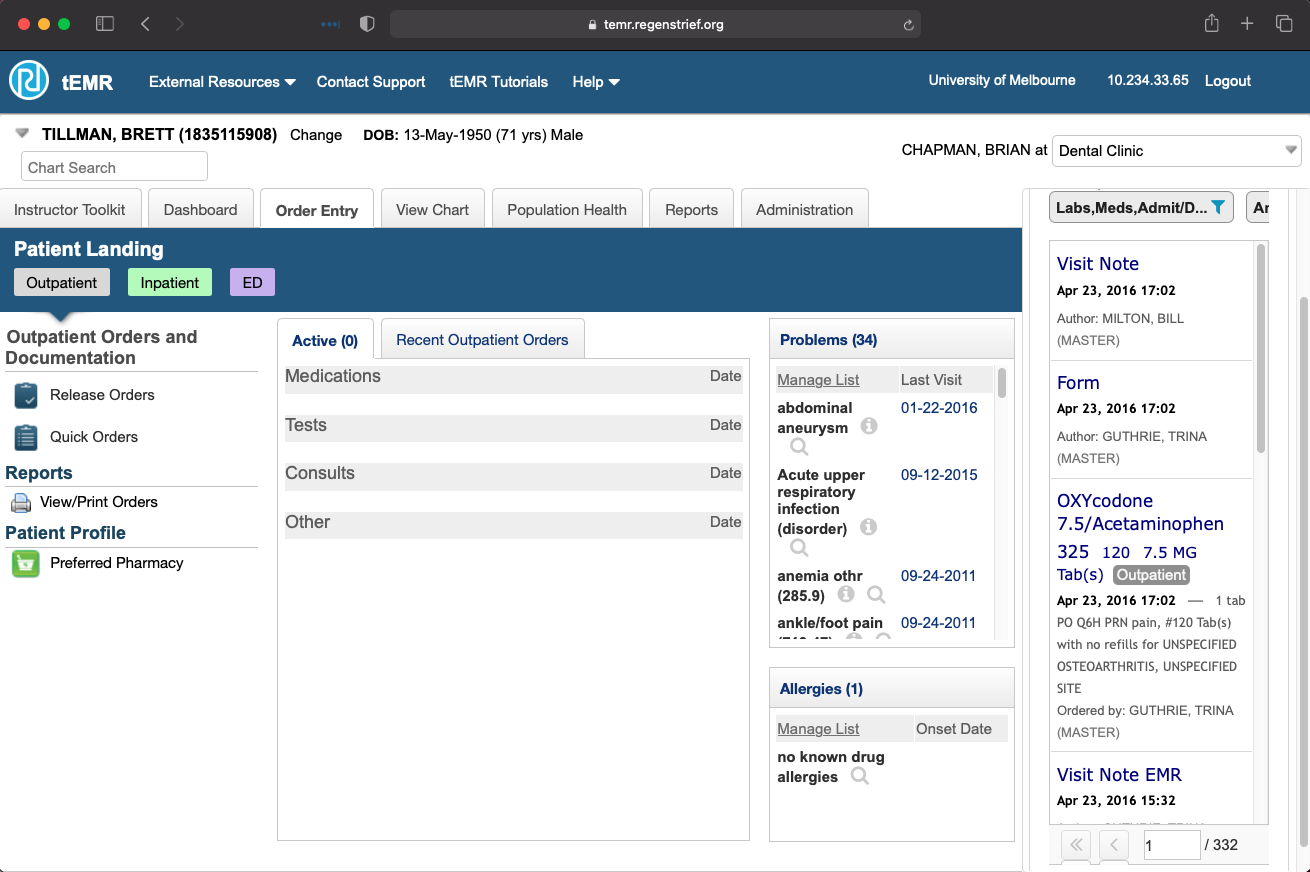

Dr. Watcher said someone from a digitally savvy generation, such as yourself, would be shocked when they first see an EHR interface. Here is a screenshot from an EHR that was formerly used for clinical care, but has now been converted into a teaching tool. What are your first impressions?

The Australian Digital Health Agency is responsible for digital health policy in Australia.

The Australian Digital Health Agency is responsible for digital health policy in Australia.

Data Retrieval in an EHR

As a physician, you will be using the EHR both to find information and to create new information via notes and orders, for example. In this next activity we are going to have you search through the charts of several patients to answer the following questions?

EHR as facilitating Communication

In the Foundations lesson, we introduced you to Dr. Peter Haug’s suggestion

“The EHR is a tool for improving both decision-making and collaboration (among caregivers, patients, and others with impact on health and well-being) in clinical care. The latter is probably more important than the former.”

We are going to illustrate these ideas by having you read through a case study where there was not an EHR available for the care of the patient. As you read through this case, we want you to examine it with the following questions in mind:

- What were the communication failures and how might a digital system (like an EHR) have helped reduce or eliminate these communication failures?

- Recalling the 5 Rights of Clinical Decision Support, can you identify examples of where an EHR or a patient portal might have helped avoid missteps in the care of this patient?

This case study was developed by Rashid Deula & Gerry Douglas of the University of Pittsburgh. If you are interested in learning more about Gerry's work in Malawi, here are some optional resources:

- FYI: TEDBlog: Fellows Friday with Gerry Douglas

- FYI: Fostering a Culture of Innovation in Malawi with Gerry Douglas

Background on Healthcare in Malawi

The Death of an African Child

- What were the key steps in the management of the patient, including prior to her hospitalization?

- What problems occurred during her management?

- Could affordable digital technologies have improved her management? If so, what and how?

On a typical morning in Sub-Saharan Africa a young mother arrived at the hospital around 9 a.m. carrying her three-month-old daughter who had been sick for some days. The previous evening the child had a high fever and was very lethargic. Unable to pay the small fee for the minibus, the young mother had to walk several kilometers to the hospital carrying her child. The child had been experiencing severe headache and fever for the past 5 days. On the 3rd day of the illness, the mother had taken her child to a traditional healer but the herbal medicine had failed to relieve the pain and fever. On the 4th day, the concerned mother tried some tablets (pain killers) she bought from a local vendor. Unfortunately, many of the tablets sold by local vendors do not have labels indicating the name of the drug or the expiration date. Sadly many of the medications are of very low quality or fake.

After taking the child’s medical history and performing a physical examination, the clinician in the outpatient department suspected severe malaria with a differential diagnosis of meningitis. He admitted the child to the pediatric ward and ordered some routine laboratory tests consisting of a lumbar puncture for cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) analysis, blood smear for malaria parasites, and a blood sample for a complete blood count (CBC) including a hemoglobin (Hb) determination. Since the presentation of complicated malaria and meningitis are similar, the clinician initiated treatment that would cover the two possible diagnoses.

The child arrived on the ward at 10:45 a.m. and the routine admission procedures were performed. The nurse on duty collected the blood samples and the clinician on the ward did the lumbar puncture that yielded clear CSF indicating no macroscopic evidence of meningitis. Nonetheless, the initial treatment from the outpatient department was maintained. The blood and CSF samples stayed in the specimen tray in the admissions room until around 3 pm when they were taken to the laboratory for analysis. Due to the high workload, in the small, inadequately equipped laboratory, the samples were not processed until the following morning. Worse still the sample for the CBC was returned because the chief laboratory technician said that the sample was clotted. Additionally, the patient’s clinical data was missing from the order form. The technician commented, "For quite some time I have been emphasizing the importance of completely filling in the order form. Since it seems that the people in the clinical units are not listening to us, we try to reinforce the practice by sending the forms back to the nurse so that it should serve as a reminder to our plea. Unfortunately, in the short term, it’s the patient who is the victim". After convincing the mother that the patient needed further tests the nurse managed to draw another blood sample.

Two days passed without results from the laboratory. Nobody bothered to ask for the results since the patient’s condition did not deteriorate. That evening at 11 pm, the child began convulsing. This surprised the mother since the child appeared fine earlier that day. She rushed to the night nurse who alerted the clinician on call. Since the clinician was busy with another emergency admission at that time he informally [verbally] ordered slow intravenous anticonvulsant (diazepam). After 60 minutes he came to the child’s bed and asked for the chart to review his medications. He noted that the patient was being treated for meningitis and complicated malaria, but he could not see the results of all the samples that were taken on the day of admission. An attempt to get the patient’s results from the lab was made immediately but no one answered the phone in the laboratory. He later went to the laboratory himself to check for the results. Flipping through all the recently documented results in the laboratory logbook, he managed to find the results for the malaria, which were negative. However, no CSF results could be found. Worse still the sample itself could not be traced. It would be necessary to repeat the lumbar puncture. Unfortunately no spare lumbar puncture kits were available and the central sterilization department was closed for the day. He communicated to the mother that the patient would continue with the current medication and everything concerning the CSF results would be sorted out the following morning.

The next morning, the clinician was still unable to obtain the results of the CSF. Since the results for this patient were not available the only alternative was to take another CSF sample, although this procedure is a painful one that no patient would want to experience more than once. The doctor told the child’s mother that he needed to do another lumbar puncture on her daughter because the previous CSF sample was somehow misplaced. She did not take this news well. Regardless, the doctor continued. Two minutes after finishing the procedure the patient convulsed again. The mother started weeping while blaming the doctor who had just done the lumbar puncture. This time the doctor personally carried the specimen to the laboratory.

By the afternoon the results were known. The child had tuberculous meningitis1. The plan was to modify treatment to cover for the isolated organism. However, the condition of the child kept on deteriorating until on the second day after the confirmed diagnosis, when the child passed away. “The hospital has killed my little girl”, could be heard in the mother’s cries of mourning.

-

The treatment for TB meningitis is very rigorous and it differs from the ordinary treatment for bacterial meningitis↩

Questions to Consider

- What are examples of communication breakdowns that you imagine an EHR might have helped avoid?

- Where might an EHR have been able to provide decision support, for example by prompting/reminding people to check for data/take actions?

Helping Data Help You

Also in the Foundations lesson we mentioned that we want an EHR to consist of something more than digital paper, that we wanted to, as much as possible, create computable data. Computable data is often referred to as structured data as opposed to unstructured data.

In this context, structured data data represented using the appropriate medical standard

Creating Data in the EHR

Larry Weed: Getting the database correct

The practice of medicine is the way you handle data and think with it. And the way you handle it determines the way you think. (Larry Weed Emory University)

Geoff Hebbard: Making Documentation more Meaningful with the EHR

ECG Data

Adapting these notebooks to illustrate working with ECG data.

ECG data exploration with systole

- Cardiac signal analysis

- Detecting cardiac cycles

- Detecting and correcting artifacts

- Heart rate variability

- Instantaneous and evoked heart rate